Getting into the tunnels was something truly remarkable. Through Randy Gaulke of meuse-argonne.com I connected with the Les Amis group and got into a tour in the summer of 2018 with my stepson Lee of the Viking Age Podcast, my Army brother Chuck, and my good friend Michiel.

Getting inside Vauquois was one extraordinary afternoon in a trip of extraordinary days. It was an experience that I will never forget, and it’s right up there with being at LTC Driant’s command post at the Bois des Caures at the exact minute of the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Verdun, and it’s up there with being able to stand in the foxholes of the Lost Battalion near Charlevaux Mill.

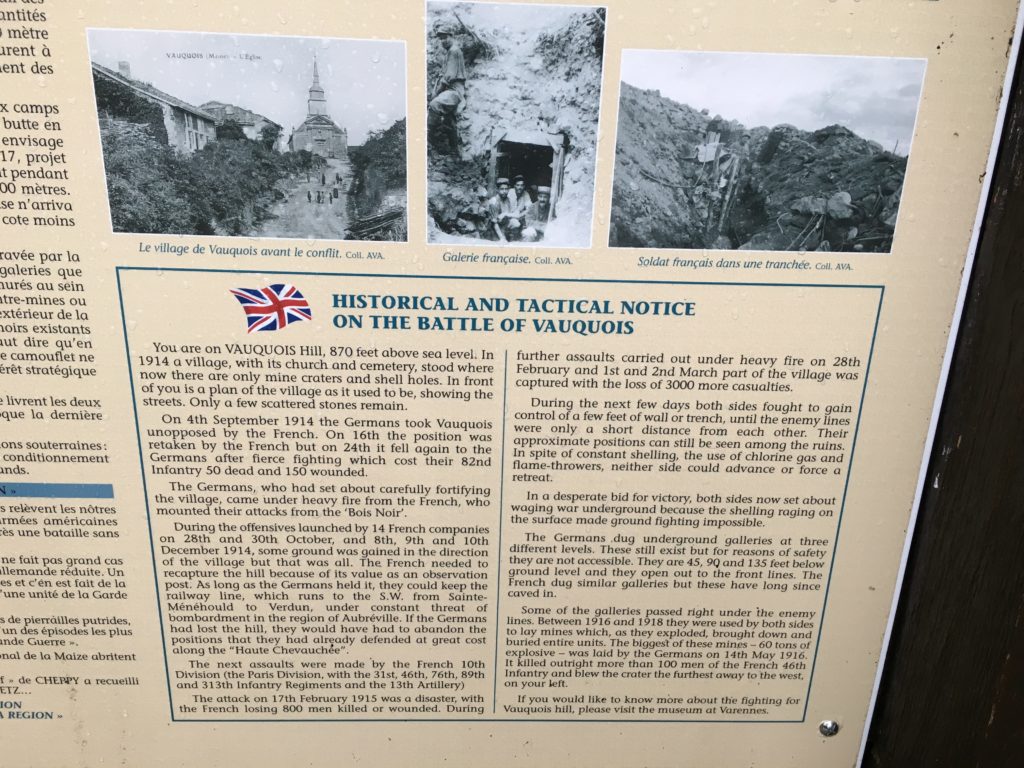

We entered the tunnels through a small 4ft by 4ft doorway at the end of one of the German trenches, and you had to enter hunched down and backwards in order to step down into a damp passageway.

Once inside this first tunnel we entered a dimly-lit world of hand-hewn tunnels that had wiring along the walls for lights and German street names at the corners.

Hand-hewn tunnels on the German side of the hill. The rock walls are gaize, a siliceous rock that is stable and flexible for digging through when damp.

My man Michiel touching the walls. It’s a moving experience to be where men a century ago lived and died.

The tunnel height makes taller folks have to stoop. It was also an instinctive thing for me to do–not that I’m that tall. But my brain said, “Tunnels. Stoop.”

Single light bulbs illuminate the passages. It’s a dim world down there.

Wiring along the walls. I’m not sure that much has changed since the Great War.

Chuck moving through ahead of me. Now he is much taller and definitely had to hunch down.

A passage leading to another hallway.

The signs are new, but the names are not. The Germans named their tunnels with street and place names from back home to help with getting around.

Remnants of German tar paper put up to make some of the underground rooms more comfortable.

Monsieur Guy Bigorgne led us through a tour of tunnels and rooms where bunks and tables sat, along with equipment and gear collected. In some of the rooms it looked like the bottles and tools were as the French and Germans had left them a century before.

Some of the bottles and utensils are from the time of the war.

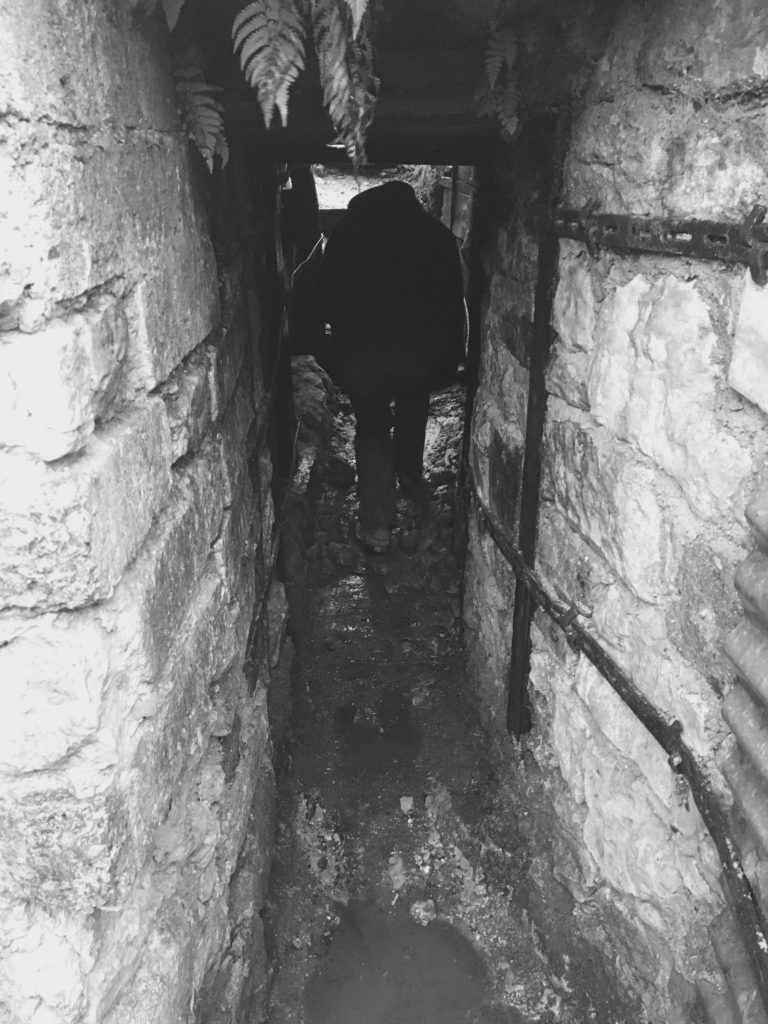

Wartime photo of French officers sitting in one of these underground rooms.

On the French side, the tunnels were supported.

Wartime images of life on Vauquois.

Duty on “Les Mont des Morts.”

A mine gallery on the French side.

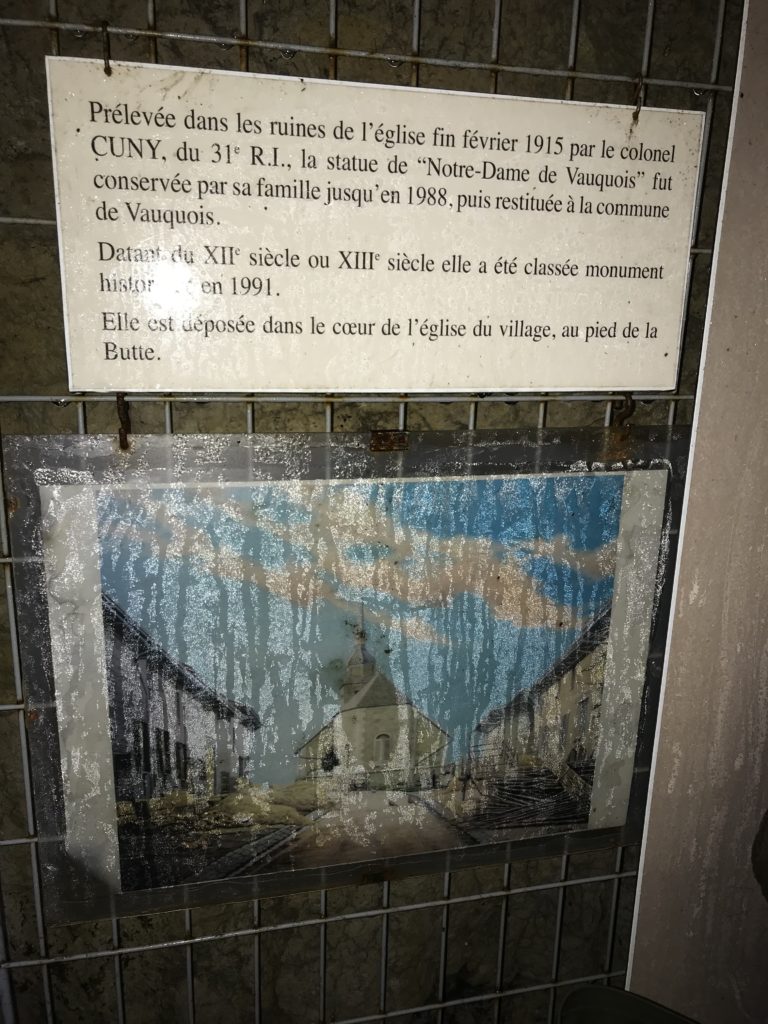

Vauquois village before the war.

A French light rail tunnel leading outside.

A German engineer in a mine gallery.

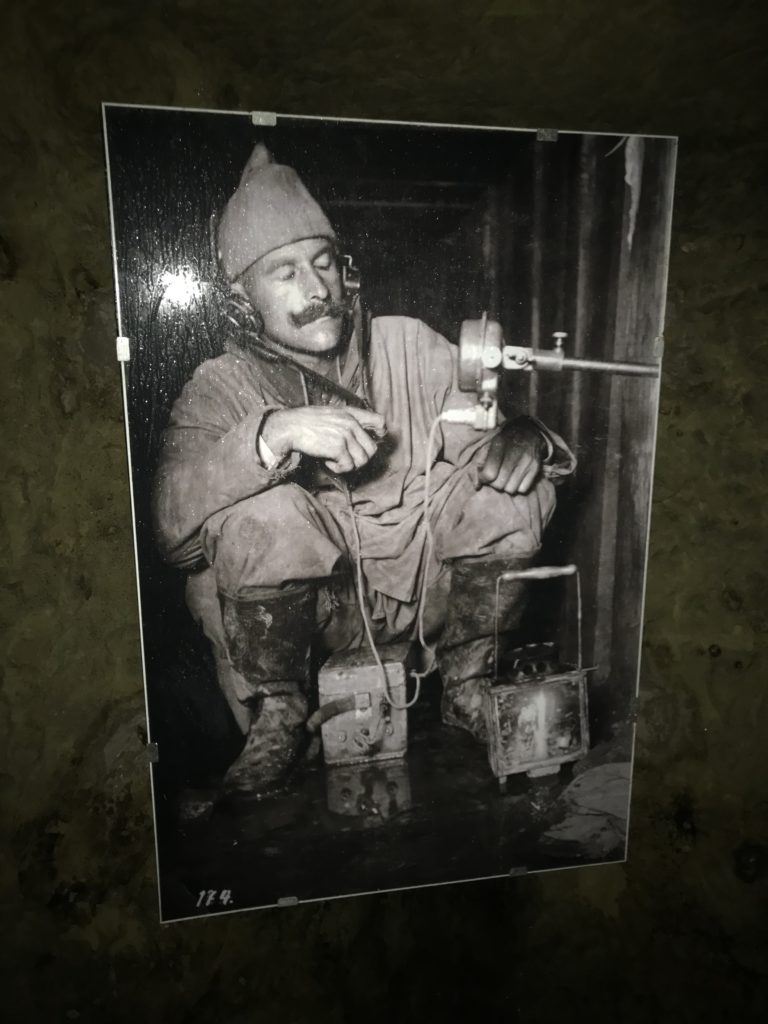

A Frenchman listening for mining noises from the enemy.

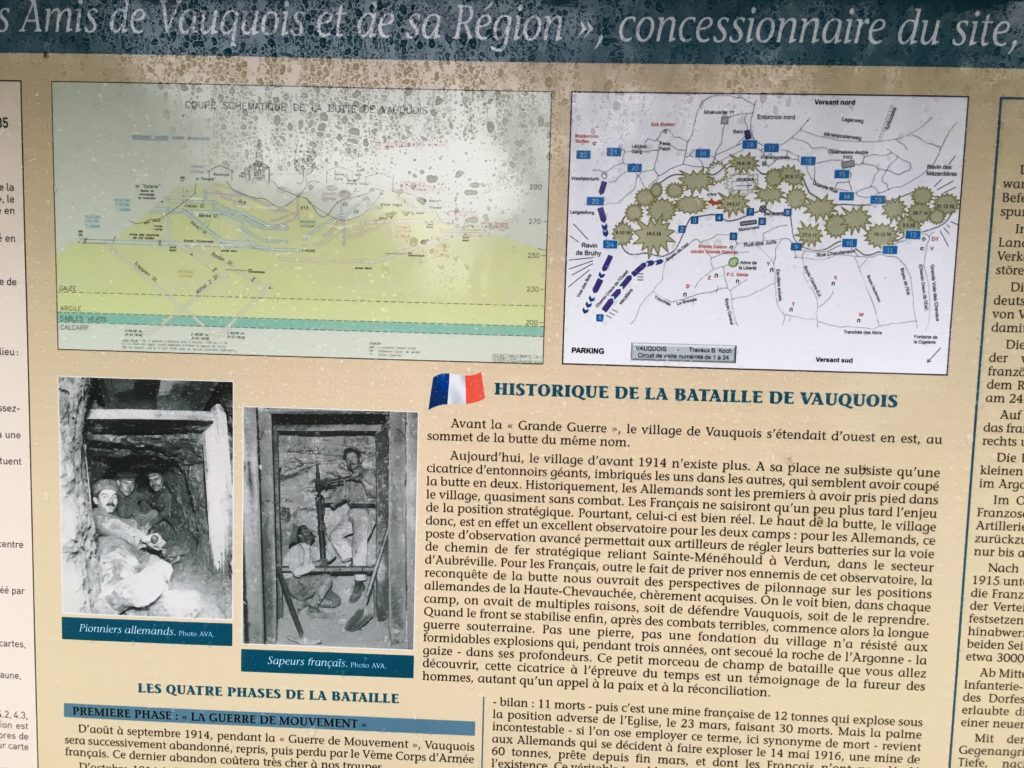

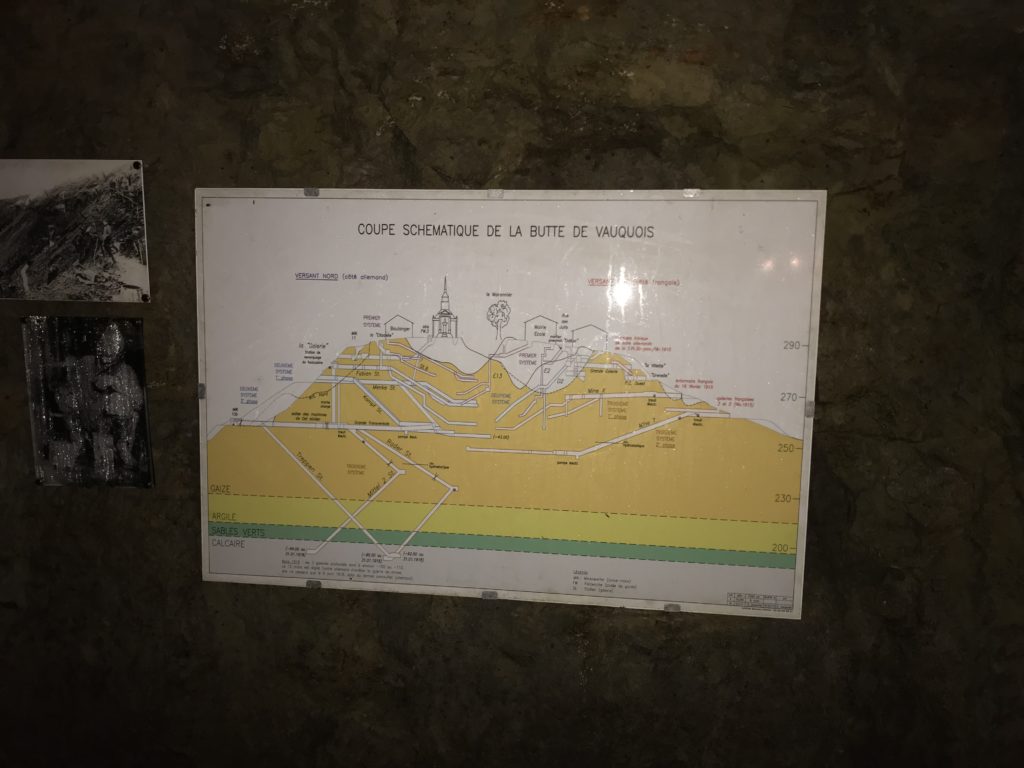

Schematic of the various tunnel systems inside Vauquois.

Heading back outside after a couple of hours underground.

What it must have been like for the men who had to live in that hill. At regular temperature the tunnels were about fifty degrees Fahrenheit; a little chilly for just a t-shirt and fishing shirt. During the war, the air inside the underground complexes would have been the same chilly norm with pockets of hot air in rooms where pumps and other machinery worked. The air would have been stale with earth, exhaust fumes, sweat, and human waste. The air must have been nauseating at times. The French tunnels featured wooden supports, along with low tunnels that supported a light railway cart system for the removal of earth and rock from the mine galleries. On either side of the hill though, the accommodations shed light on the dark troglodyte world these men endured for years on end.

Michiel walking through the French trenches.

Lee walking through the French trenches.

Supported trench works.

It’s hard to tell, but under the corrugated metal is a set of steps–this was where a building of the ancient hilltop village was incorporated into the trench lines.

The construction helmet provided by Les Amis de Vauquois and mandatory for underground tours.

It was a wonderful tour, and Guy Bigorgne said himself that he is a talker and thus his tours are generally longer than those of the other guides. I could have listened to him for days, he has a remarkable wealth of knowledge and his passion for the subject of Vauquois is evident.

If you ever visit the Verdun and Meuse-Argonne battlefields, do make a stop at Vauquois. This is a site left largely untouched since the end of the Great War, and the ground stands in silent agony there. Even a walk across the tortured summit is well worth it. You’ll feel the war up close.

So…the only way to finish this post is with my man Chuck’s words down in the tunnels: