Not everyone felt the same way Wilfred Owen did during the Great War; some men felt the war was their duty to do. They did it and that was it.

For others however, Wilfred Owen captured the war in all its horror and pity–in his own words, “the poetry is in the pity.” Today marks 100 years since this 25-year-old man was killed in action in the last days of battle on the Western Front, though no one at the time was quite sure of that. He was not the only young man to die that day. Yet we remember him as one of the voices that tried to convey what it was like to live through this devastating Great War.

A century since his death. A century since a rising voice in British and world literature was extinguished far too early, along with thousands of others like him.

Below is the poem called “The Sentry,” which was used for the last episode of the Somme podcast episodes. For several years now, thanks to an audiobook titled “In Flanders Field ad Other Poems About War,” that poem has haunted me for its intense setting and visual language. It is the poem I’d like to highlight on the centenary of Wilfred Owen’s death.

The Sentry

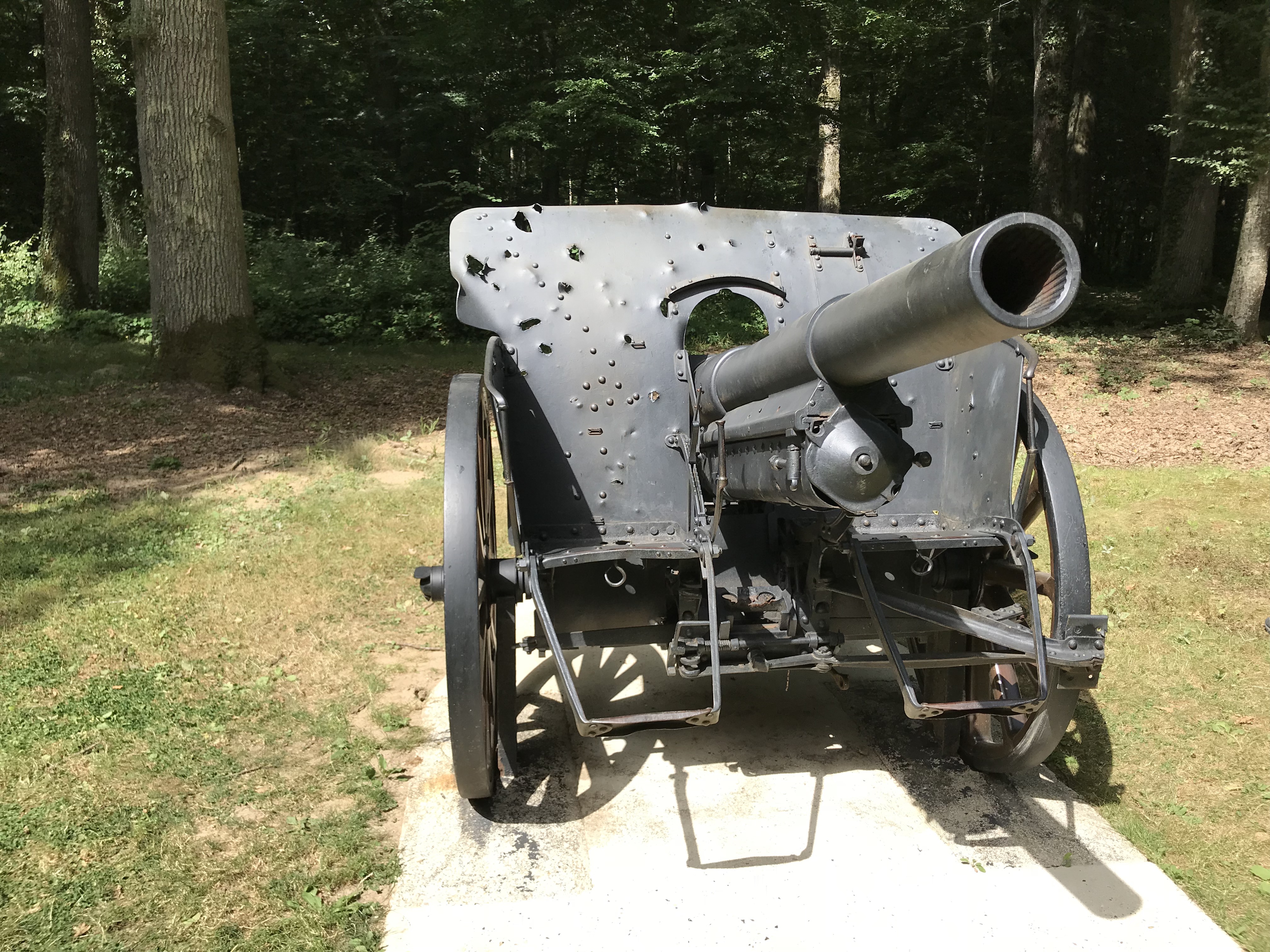

We’d found an old Boche dug-out, and he knew,

And gave us hell, for shell on frantic shell

Hammered on top, but never quite burst through.

Rain, guttering down in waterfalls of slime

Kept slush waist high, that rising hour by hour,

Choked up the steps too thick with clay to climb.

What murk of air remained stank old, and sour

With fumes of whizz-bangs, and the smell of men

Who’d lived there years, and left their curse in the den,

If not their corpses. . . .

There we herded from the blast

Of whizz-bangs, but one found our door at last.

Buffeting eyes and breath, snuffing the candles.

And thud! flump! thud! down the steep steps came thumping

And splashing in the flood, deluging muck —

The sentry’s body; then his rifle, handles

Of old Boche bombs, and mud in ruck on ruck.

We dredged him up, for killed, until he whined

“O sir, my eyes — I’m blind — I’m blind, I’m blind!”

Coaxing, I held a flame against his lids

And said if he could see the least blurred light

He was not blind; in time he’d get all right.

“I can’t,” he sobbed. Eyeballs, huge-bulged like squids

Watch my dreams still; but I forgot him there

In posting next for duty, and sending a scout

To beg a stretcher somewhere, and floundering about

To other posts under the shrieking air.

Those other wretches, how they bled and spewed,

And one who would have drowned himself for good, —

I try not to remember these things now.

Let dread hark back for one word only: how

Half-listening to that sentry’s moans and jumps,

And the wild chattering of his broken teeth,

Renewed most horribly whenever crumps

Pummelled the roof and slogged the air beneath —

Through the dense din, I say, we heard him shout

“I see your lights!” But ours had long died out.

Lest We Forget.

Photo courtesy of Imperial War Museum.